When Tash Jamieson made it her mission to make studying fun for her stepson Drake, she had no idea she was building the first iteration of edtech startup Lockpick Games.

This was back in mid-2021. Ten-year-old Drake was struggling at his local school, despite being a talented and bright kid, and Tash and her partner Jeff determined he needed an environment that would challenge him. Private school fees were financially inaccessible, so the pair decided to prepare Drake for the New South Wales selective school entry examination.

“When we started trying to get him to engage in the process of studying, he just didn't want a bar of it,” Tash explains.

“Here we were telling him he couldn't play video games or soccer, but instead, had to stay home and do math tutoring. He just completely disengaged with the process.”

Tash and Jeff decided to make the learning process more fun, creating a ‘choose your own adventure’ book, in which the characters asked questions linked to skills required for the entry exam.

“The first time we tried it with Drake, he said he had a headache and felt sick,” Tash reflects, laughing a little.

After some prompting, however, Drake explained the book wasn’t a real game because he couldn’t control it, and it wasn't actually fun because he knew he was learning. This was Tash’s lightbulb moment.

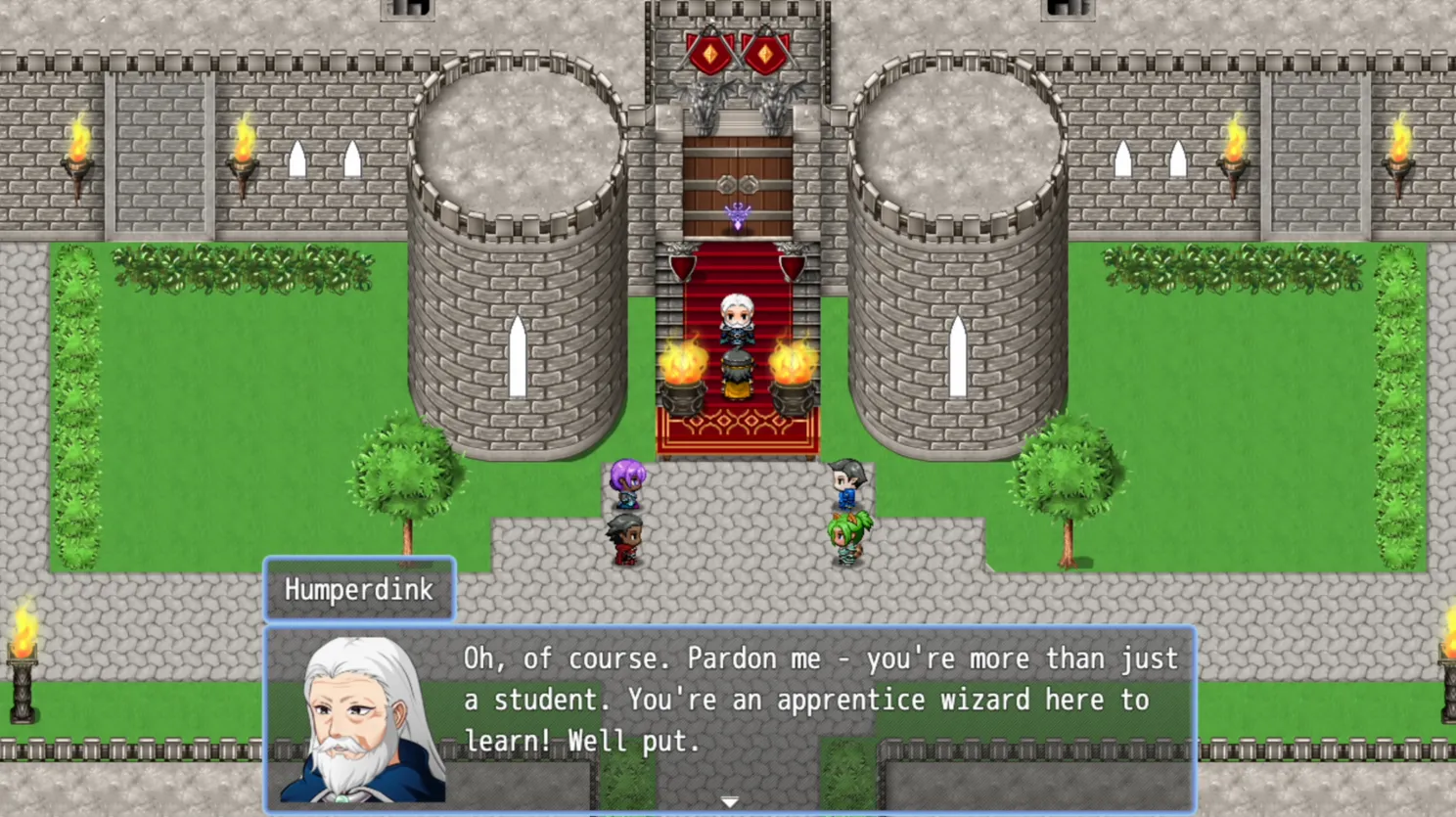

“We started experimenting with creating a video game, and eventually, we built a demo version of Marble Mansion,” Tash says.

“When we showed it to Drake for the first time, he spent four hours straight playing the game and got through 56 questions from the test we were trying to study for.

“He was laughing and giggling the whole time. He literally went from pretending to be sick, to actually engaging.

“I started thinking about the game, and figured, we can’t be the only parents who have this problem. I know heaps of kids who just don't learn in these traditional tutoring environments.”

Examining standardised testing

The intention of selective schools is to extend opportunity to talented students who don’t have the financial means to go to the best schools.

On paper, selective schools improve access to education and fight inherited equity disparities. But when you look a little closer, not everything is as it seems, Tash tells me.

“If you look at the financial backgrounds of the kids who sit the New South Wales selective school exams, 59% are from families within high socioeconomic brackets or who have at least one parent with a bachelor's degree or above,” Tash explains.

“When you look at who gets accepted into these selective schools, you’ll see 64% are from high socioeconomic brackets.

“It blows your mind.”

At this point, Tash adds a caveat.

“I’m not saying there is anything wrong with educated parents chasing better opportunities for their kids. Jeff and I both have degrees. We are that family.

“My point is that access to these selective schools is really based on your financial resources.”

For example, despite having two degrees to her name, Tash couldn’t help Drake study for the exam’s “bloody hard” algebra component. She was fortunate she could afford to hire a private tutor for $100 a week, but soon learnt some parents are spending up to $20,000 on tutoring services annually.

“When you realise that the students who actually need these spots are not getting them, it makes you stop and think. There are so many subtle barriers that stop kids from just being who they need to be in the world,” Tash says.

But this problem is bigger than a New South Wales selective school exam. The SAT and IELTS exams are also dominated by those with disposable financial resources, for example. This is a global problem. We need to ensure all students globally can adequately prepare for standardised tests, Tash says.

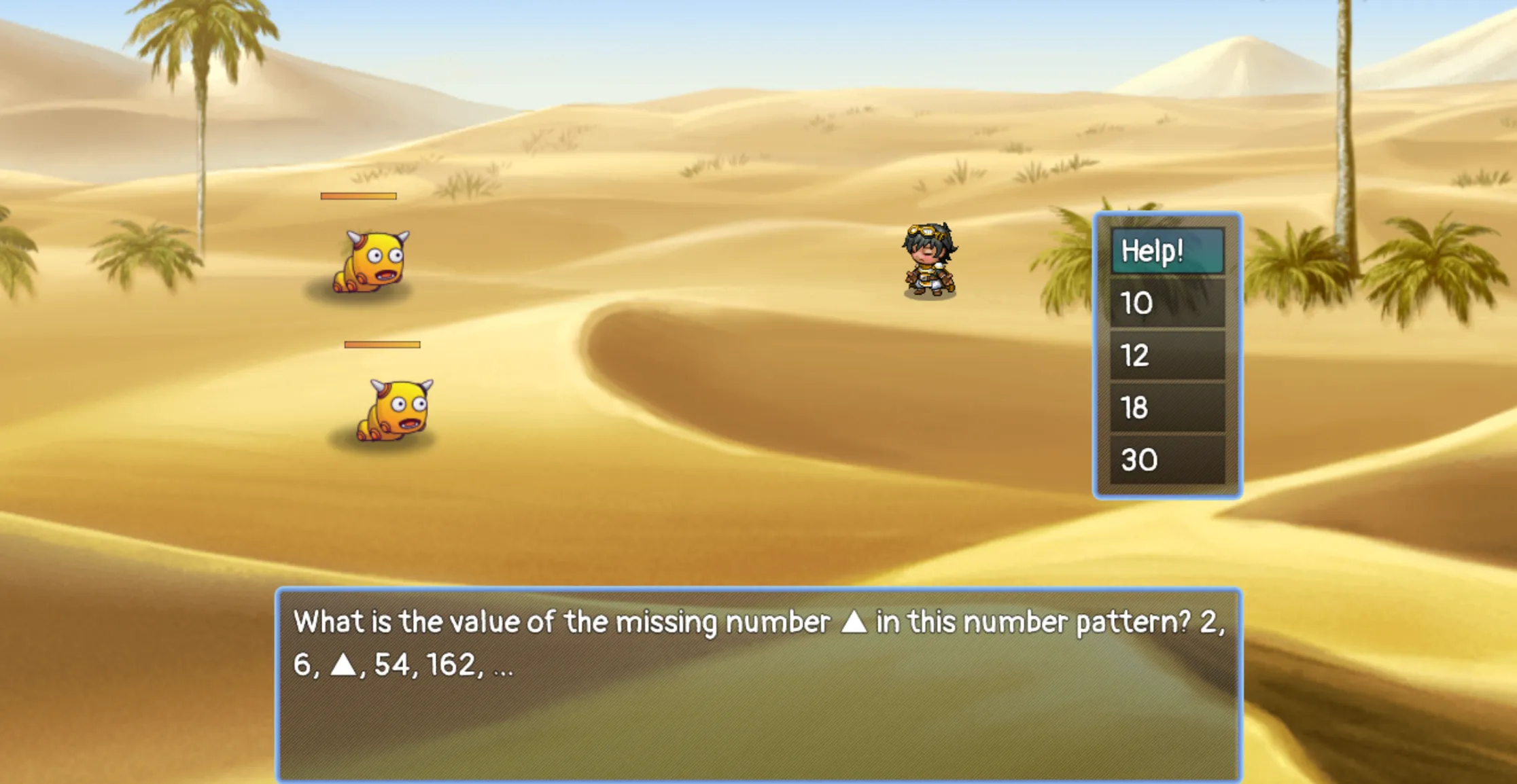

“And this is without even talking about how standardised tests in general are designed for neuro-typical kids and adults. A video game can resonate with people who absorb information differently,” Tash adds.

“Drake's brain just better engages with this form of learning — not because he is less capable with the subject matter, but rather, because of the way it is presented.”

Learning to “get your stuff out there”

The most valuable thing Tash has learnt since becoming an edtech founder isn’t pitching, designing or coding — but rather, how to embrace getting feedback on a far-from-perfect product.

When Tash was going through the Founders Fellowship, she attended a session run by EntryLevel Founder Ajay Prakash.

“He said: ‘Get something out there that you can charge people $1 for to see if there's interest. If you can get something up in the next 12 hours, I will give you my time, and give you feedback’,” Tash says.

“So I stayed up until midnight, made a Lockpick Games landing page, and posted in a parents’ studying Facebook group. The next morning I woke up to 75 email addresses from people asking for the game.”

When Tash sent out the game, she started getting feedback — some of it glowing, some of it constructive, all of it valuable.

“One parent wrote back and said his son had been really down because of lockdown and homeschooling and the game was his one relief this week.

“Someone else wrote back and said ‘there are no instructions, I have no idea what to do’. That was a huge oversight on my part and really helpful feedback.”

Once Tash started receiving feedback, she realised that even “in its really crappy infancy” the game was adding value to kids and providing a joyful escape from a really arduous process. The prototype might not have been perfect, but it perfectly proved Lockpick Games’ potential.

“Just get your stuff out there,” Tash advises other early-stage founders.

“Once it’s out there ... it’s so motivating because it’s no longer theoretical. You’re suddenly helping solve someone else’s problem too.”

%204.webp)

.png)